The wikipedia entry about the New World Translation (which I will return to from time to time) takes a jab at John 17:3 "the term taking in knowledge' rather than "know" at John 17:3 to suggest that salvation is dependent on ongoing study." That is, we must question the motives behind such a translation rather then investigate whether that is an allowable translation (a standard never applied to the mainstream/swamp Bibles).

W.E. Vines Expository Dictionary states that GINOSKO (1097) means, "to be taking in knowledge, to come to know, recognize, understand." Strong's also uses the word "in a great variety of applications with many implications", which, if you look this scripture up in the Amplified Bible will see that it renders it, "to know (to perceive, recognize, become acquainted with and understand.)

Vincent's Word Studies in the New Testament adds here: "Might recognize or perceive. This is striking, that eternal life consists in knowledge, or rather the pursuit of knowledge, since the present tense marks a continuance, a progressive perception of God in Christ."

Roberston's Word Pictures says of John 17:3, "Should know (gino¯sko¯sin). Present active subjunctive with hina (subject clause), 'should keep on knowing.'"

The Abingdon New Testament Commentaries writes: "For 1 John as well as the Fourth Gospel (John 17:3), the knowledge of 'the only true God' whom Jesus reveals gives eternal life."

Thayer's Lexicon says of GINWSKW: "to learn to know, to come to know, get a knowledge of"

Mounce's Basic's of Bible Greek says of GINWSKW: "come to know, realize, learn."

Also "eternal life is bound up with the knowledge of the Father, the only true God" [William Kelly Major Works Commentary]

Weymouth's The New Testament in Modern Speech adds in the footnote: "knowing]Or, as the tense implies, 'an ever-enlarging knowledge of.'"

"Faith involves knowledge. The Christian faith, therefore, does not contain an ounce of blind faith. The Bible teaches that in order to have real faith one must have true knowledge. [Systematic Theology Made Easy By C. Matthew McMahon]

"Knowledge of God is indispensable, self-knowledge is important, knowledge of others is desirable; to be too knowing in worldly matters is often accessory to sinful knowledge; the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ is a mean of escaping the pollutions which are in the world (John xvii, 3)." Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature By John McClintock [p. 136]

Henry Alford's The New Testament for English Readers ties 2 Peter 1:3 ["seeing that his divine power hath granted unto us all things that pertain unto life and godliness, through the knowledge of him that called us by his own glory and virtue"] with this footnote, "the knowledge of God is the beginning of life, John xvii. 3. Calvin)"

"'This is life eternal, that they should know Thee the only true God, and Him whom thou didst send, even Jesus Christ' (John xvii. 3). Through this knowledge believers escape the defilements of the world (2 Peter ii. 20), and all increase in grace is effected by a deeper knowledge. The Greek word is emphatic (epignosis) signifying “ a steady growth in knowledge, an advance step by step, not knowledge matured but ever maturing” (LUMBY). Peter uses this word four times in this Epistle (here, i. 3, 8; ii. 20)." The Lutheran Commentary edited by Henry Eyster Jacobs 1897

"Eternal life is the never-ending effort after this knowledge of God." The Epistles of St. John: The Greek Text By Brooke Foss Westcott [p.196] 1905

"The difference between oida and ginosko is worth considering a little further, as follows: Oida is immediate perception. Ginosko is gradual knowledge." The Knowledge of God, Its Meaning and Its Power By Alfred Taylor Schofield 1905

Raymond Brown in his Anchor Bible writes: "they know you. Although some witnesses have a future indicative, the best witnesses have a present subjunctive; this implies that the knowledge is a continuing action."

"And the eternal life is this: to obtain a knowledge of You the only true God, and the Messiah Whom You have sent." Ferrar Fenton's The Complete Bible in Modern English

It may be that the NWT translates this verse better than most other Bibles. The New World Translation also carefully notes the difference between gno'sis ("knowledge") and e·pi'gno·sis (translated "accurate knowledge")-a difference ignored by many others. (Philippians 1:9; 3:8)

......................

"'This is life eternal, that they might know Thee;' not the truth merely, not the gospel, but Thee. And this throws light upon the nature of the knowledge here spoken of —the nature of that intellectual element which we have shown to be an essential ingredient in personal Christianity. You will observe that eternal life is connected with the knowledge, the simple knowledge, of God and Christ. Now, are we not at first rather stumbled at this? We say, How can this be? Do we not find persons possessed of the knowledge of Christianity, who have no spiritual life in their souls? And how do we meet this apparent contradiction between Scripture and actual experience? We say, their knowledge cannot be of the right kind; it is not saving knowledge, it is not spiritual knowledge, and so on. And, therefore, with the view of correcting the text of Scripture, and preventing the abuse of it, we read it thus:— This is life eternal, that they might savingly, spiritually know thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom thou hast sent. But there are no such words as savingly and spiritually in the original, and surely if they had been necessary they would have been introduced. Our Saviour's words are simply, that they might know. Would it not be better, therefore, instead of almost always directing people's minds to the act itself of knowing, to direct them more frequently rather to the object—the Person to be known? This would determine the nature of the knowledge required, as well as call it into exercise. Scripture does not define, at least in any formal way, either faith or knowledge; and the explanation is this—it sets before us the proper objects of faith and knowledge, and trusts to their making, when realised, the right impression upon the mind. It does not tell you how to believe, or how to know. How could it? It could use no definition that would not leave the matter as great a mystery as before. Besides, this would have been drawing away our regards from the truth itself to the operations of our own minds. What, then, is the explanation of our now-a-days deeming it necessary to guard those simple words, faith and knowledge, from abuse, by qualifying them, and making additions to them? It is this: We have too much lost sight of their proper objects. We have overlooked too much this personal element. We have dealt too exclusively with abstract doctrines, which in their own nature cannot give birth to anything but purely abstract and dialectical states of mind; and so we need to draw distinctions, and to speak of saving and speculative faith, saving and speculative knowledge— distinctions which are quite unintelligible to those for whom they are designed, just because the spiritual character of those acts presupposes the spiritual character of their objects. It is life eternal to know THEE. Ah! there lies the secret of that knowledge which is eternal life. I must either know Him, or not know Him. There is no middle state of mind. If I have not the knowledge which is eternal life, it is not the true God and the true Christ that I have been contemplating, but a figment of my own imagination—an unsubstantial conception of my own mind. True, the knowledge of a divine and spiritual being must needs be a spiritual knowledge, the result of a spiritual influence upon the mind. But here, as in every other department, the nature of the knowledge depends primarily on the nature of the thing known; and we do think that by far the most effectual way of dealing with the unrenewed is, instead of telling them that they do not know aright and believe aright, to assure them that they do not believe and know the God and the Saviour of the Bible at all."~Christianity a Life: a sermon By Alexander L. R. Foote 1853

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Saturday, June 27, 2020

Mormon Leader Joseph Smith on This Day in History

This Day In History: Mormon leader and founder Joseph Smith was killed on this day in 1844. The Mormons are a fascinating enigma. They are very nice people that have attracted some scary people, and their offshoot groups are just plain nutty. This though has made for some entertaining reading over the years, books such as, "Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer"; "The Kirtland Massacre: The True and Terrible Story of the Mormon Cult Murders by Cynthia Stalter Sasse and Peggy Murphy Widder"; "The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer"; "The Mormon Murders: A True Story of Greed, Forgery, Deceit and Death by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith"; "The Mountain Meadows Massacre by Juanita Brooks"; "Salamander: The Story of the Mormon Forgery Murders by Linda Sillitoe" etc. Much of this derives from the "One Mighty and Strong" prophecy,

Friday, June 26, 2020

A Tomb-Stone in an English Church-Yard

"Here lies ______ ______, of Trinity,

A Doctor of Divinity,

Who knew as much of Divinity

As others do of Trinity."

Sunday, June 21, 2020

The End of the World on This Day

This Day In History: According to Mayan Calendar revisionism based on the differences between the Julian and Gregorian calendars, the world will end today. Additionally, we are to have a solar eclipse today as well. While 2020 does make apocalyptic sense for obvious reasons, end of the world predictions are numerous throughout history. As the world approached the year 1000, riots are said to have occurred in Europe. Joachim of Fiore declared the end of the world for 1260, which was later revised to 1290 and then again to 1335. The Black Death in the 1300's spreading across Europe was interpreted by many as the sign of the end of times. in 1524 astrologers in London predicted the world would end by a flood starting in London, based on calculations made the previous June. Twenty thousand Londoners left their homes and headed for higher ground. Columbus claimed that the world was created in 5343 BCE, and would last 7000 years. Assuming no year zero, that means the end would come in 1658. In 1666, with the presence of 666 in the date, the death of 100,000 Londoners to bubonic plague, and the Great Fire of London led to superstitious fears of the end of the world. One of the most popular predictions was by William Miller for the years 1844/1845 which came to be called The Great Disappointment. 20th century predictions are too numerous to mention.

See also The Number 666, the Beast & the Apocalypse - Over 250 Books on DVDROM

For a list of all of my digital books click here

See also The History of the Antichrist by Lewis Spence 1920

For a list of all of my digital books click here

See also The History of the Antichrist by Lewis Spence 1920

Thursday, June 18, 2020

The Wicked Bible on This Day in History

There was also the "Party Bible" in 1716 that was supposed to read “Sin no more” at Jeremiah 31:34 but instead read “Sin on more.” A 1795 edition of the King James Bible that read "Let the children first be killed" at Mark 7:27 (the word was supposed to be "filled"). In a 1763 printing, Psalm 14.1 says: “The fool hath said in his heart there is a God,” when there should be a “no” where the “a” is.

There are also translation decisions that feel like errors, such as Joshua 15.18 in the New English Bible: "As she sat on the ass, she broke wind, and Caleb asked her, “What did you mean by that?"

See also: Bible Curiosities by William S Walsh 1893

https://newworldtranslation.blogspot.com/2017/10/bible-curiosities-by-william-s-walsh.html

Printing Errors in Bible Versions by Henry Barker 1911

https://newworldtranslation.blogspot.com/2020/03/printing-errors-in-bible-versions-by.html

Friday, June 12, 2020

Popular Books among the Jews in the Time of Christ

Popular Books among the Jews in the Time of Our Lord by the Rev. Professor Allan Menzies, D.D., St. Andrews

See also Over 100 Lost, Hidden, & Strange Books of the Bible on DVDROM, and Over 180 Forbidden & Lost Books of the Bible on CDROM

For a list of all of my digital books and disks click here

IT is of great importance to the student of the New Testament, and especially to the student of our Lord's life, to know what the Jews were thinking and expecting in Jesus' time. The latest book of the Old Testament dates more than four centuries B.C. In what direction did Jewish thought travel during these four centuries? The ideas and wishes of the contemporaries of Christ can scarcely be identical with those of the Old Testament, any more than the ideas even of the most conservative among ourselves are identical with those which are expressed in the Westminster Confession of Faith. Thought never stands still, and it did not stand still with the Jews, even when the age of prophecy was past. In the Gospels, accordingly, we find ourselves in a very different world from that of the prophets of the Old Testament. Circumstances have changed, new ways of thinking have appeared, new figures move before the eye of faith, new hopes are felt. The current belief of the Jews in Christ's time differs from the current beliefs of the time of Ezra, about such subjects as angels, the future life, the Messiah, and many others, in a way which every one must at once recognise.

Where can we learn what were the current ideas and beliefs of the Jews at the beginning of the Christian age? The New Testament itself, of course, tells us a great deal about this; but on many

points it excites rather than satisfies our curiosity. You cannot, for example, construct from the Gospels the belief the Jews entertained about the Messiah. Various notions of the Messiah cross

and recross each other there; at one point the Messianic question seems to be one of intense interest to the fellow - countrymen of Jesus, at another they seem to care very little about it; it is

hard to make out whether or not they knew what Jesus meant when He called Himself the Son of Man. If we could gather from sources outside the New Testament what state of mind these people were in, and what ideas they had, a flood of light would be cast on the Gospel narrative.

Now, one learns what a people think from the books which are written and read among them. And the study of Jewish literature has lately been assuming far more importance than before for the reader of the Gospels. In the Jewish books, it is felt, we may learn what people were thinking when Jesus came, and so Jewish literature is being ransacked by those who deal with the life of Christ; and we are likely to get plenty more of it.

It has been the Rabbinical literature to which most of this attention has been directed. In the Rabbinical literature we have the scholastic learning of the Jews, the learning which the scribes carried on in their schools. Certain methods are used in dealing with Scripture which lead to the development of laws and practices not enjoined in the law; the system of the tradition is built up, and every subject of interest is treated according to fixed rule. Recent lives of Christ are full of Rabbinical quotations; by these, it is supposed, we learn what the Jews thought about the forgiveness of sins, about the world to come, about the Messiah and His forerunners, and so on.

The two works before us deal with a widely different branch of Jewish literature. The labours of the scribes, indeed, were not committed to writing in Jesus' day, they did not form books at all till several generations afterwards; but there were books in His day, written not long before, and expressing popular ideas and hopes in a way the labours of the scribes could never do. The discussions of the scribes originated in the world of learning, and appealed mainly to the learned; but in the other literature we speak of, imagination played a much greater part than learning. The spirit turned from the humiliating present to a future in which Israel should be freed from all humiliation, and set on high above all enemies; it turned also from the dry, formal discussions of law to a region in which thought was free, and could fashion the course of events to its desires. It is one of the strangest contrasts to be seen in any part of history, that at the same time when the scribes were seeking to embrace the whole of life in a great set of regulations, the imagination of the people, free from all restraints, whether of past history or of present likelihood, was painting splendid pictures of the future of Israel in the Apocalypses.

Of the apocryphal books which formed part of the Septuagint, and are printed in many English Bibles, very scanty traces are to be found in the New Testament; it appears that these books, which

were written in Greek, and in which the Messianic hope is strikingly absent, were little read in Palestine. Of the various Revelations, however, there are many evidences in the New Testament; in the short Epistle of Jude, two of them are referred to, Enoch and the Assumption of Moses, in the passage about the body of Moses. The sawing asunder of Old Testament martyrs, mentioned in Heb. xi., is taken from the "Ascension of Isaiah." And several other instances might be mentioned.

These books form a very curious literature. The name "Pseudepigrapha," or "Falsely named," by which they are often distinguished, is derived from the fact that each of them assumes the name of some Old Testament worthy. Sometimes it is the account of the ascent of such an one to heaven, of what he saw there, and of the predictions that were there put in his mouth; thus we have the

Book of Enoch and the Ascensions of Moses and of Isaiah. Sometimes the seer of old gives his prophecy to his posterity as his last legacy; thus we have the Testaments of the Three Patriarchs, of

the Twelve Patriarchs, and of Moses. Sometimes a revelation is made to a character of the Old Testament in his lifetime; thus there is the Apocalypse of Baruch, of Ezra, and of others. There are also many pseudepigraphic works of a legendary character, in which the element of prediction is less pronounced, such as the "Book of Jubilees" or the "Little Genesis," the Book of Jannes and

Jambres," mentioned by Origen, but not now extant, etc. This literature deals largely with the future. Most of the books are apocalyptic in their character-that is to say, they predict the future, not in the grand undefined way of the older prophets, but precisely, dealing with dates, figures, and measurements, and long chains of events to happen in this exact succession.

Click here to go to Over 180 Forbidden & Lost Books of the Bible on CDROM

Here, then, we have a set of books as different as possible in spirit and method from the scholastic Rabbinical literature which has often been regarded as the one sole source, outside the Bible,

of our knowledge of Jewish thought in our Lord's time. From these strange works, we learn how the Jew felt and thought who had not offered himself up entirely to the study of the law, and how there was a growth of thought in Palestine which was not the direct outcome of that study nor in bondage to it. No wonder that scholars are turning with eager interest to this branch of Jewish literature, which appears to put before us the thoughts and aspirations of a freer and more living section of the Jewish nation than were the scribes and Pharisees.

Of the books of this nature which may now be read, the majority have come to light but recently. The Book of Enoch, for example, was first edited, in Ethiopic, in 1838; the Book of Jubilees, also in Ethiopic, in 1859; the Ascension of Moses in 1861. Thus we are only beginning to realise the nature of a literature the study of which no one can doubt must have a great influence on our understanding of the gospel narrative. Before any theory can be framed of the relation between the ideas of these books and those of the Gospels, before any history of Jewish thought can be constructed out of them, criticism has to do its work upon them; and it cannot be said that critical discussions of their date, their original language, the meaning of their dark and enigmatical figures and impersonations, are by any means at an end. In Mr. Deane's excellent book, Pseudepigrapha, it is these questions that claim our attention. This book consists of a set of essays written at different times, in each of which one of these works is discussed, and which are now collected into a volume. Mr. Deane makes no attempt to construct a history of Jewish thought out of the works he deals with; each book is taken by itself, and, after a careful and thorough statement of the history of its text and editions, as well as of the references to it in the Fathers, the teaching of the book is described, and in the most cautious way it is suggested that the book "helps us to estimate the moral, religious, and political atmosphere in which Christ lived," or that the book illustrates the point that at the beginning of the first Christian century "the expectation of a Messiah was not universal" among the Jews. Mr. Deane's book is thus a collection of critical studies, from which the inferences are scarcely drawn by him. Nor does he treat by any means all the works included in his title; for a complete list and a discussion of the whole subject, the reader will have to turn to Schurer's History of the Jewish People, or to Zockler's (untranslated) ninth volume of the Kurzgefasster Commentar of the Old Testament, in which he treats the Old Testament Apocrypha, and gives an appendix on the Pseudepigraphic literature. Within its limits, Mr. Deane's book is certainly a scholarly and useful work, which every student of

the subject will do well to possess.

Mr. Thomson's Books which Influenced our Lord and His Apostles, announces by its title that it has a theory on the subject. For this we praise him. The principle of self-denial which leads English scholars to refrain from theory, and labour at facts on which a sound theory may some day be erected, is in some degree a noble one; but it makes the studies to which it is applied very dry and uninteresting, and repels the reader who cannot follow detailed investigation, and yet wants some guidance on the subject Many cannot wait till such elaborate foundations be completed; they must have a house of some kind ·to live in, even now. And, besides, it seems to be a law of intellectual advance that progress is made by the imagination putting forth hypotheses to be proved or disproved by the facts, as they are examined more carefully.

Whether Mr. Thomson's theory will stand or no, is a different matter. With regard to his title, which is a snfficiently striking one, we had the impression at first that Mr. Thomson could not mean what his title says. Mr. Deane contends for no more than that the Apocalyptic writings give us information about the state of opinion and sentiment in the early Christian age. One might without any irreverence go further, and argue that our Lord was influenced by the views and feelings of the society into which He was born, and that these writings are evidence of the state of things He thus inherited. But that the Book of Enoch, or the Psalms of Solomon, or the Assumption of Moses were books He knew, and that they helped to lead His thoughts, this we did not suppose the writer could mean. He does mean this, however, though he does very little, so far as we have seen, to specify what elements in our Lord's teaching or attitude may have been derived from such sources. Neither in his Introduction, where he states the theory he holds on the subject, nor in his elaborate discussions of the various apocalyptic writings (where we notice interesting differences between his conclusions and those of Mr. Deane), does he seriously set himself to trace in what way our Lord was influenced by these books. The books were strongly Messianic, and our Lord uses the Messianic title "Son of Man," which is peculiar to them in the Jewish literature of the day. Other instances of contact it is said might be brought forward (but we have not noticed them). And the apostles use phrases derived from these books, and directly refer to some of them. This is all Mr. Thomson adduces in direct vindication of his title. He gives us an excellent description of the state of the Jews, and of their sects in Jesus' time; and engages in learned critical dissertations on the apocalypses, in which there is much that is of value; but we look in vain for any analysis of the teaching or of the career of the Lord which should prove that or how these works had moved Him.

Instead of this analysis, Mr. Thomson presents us with a theory of the origin of the apocalypses, and of our Lord's external connection with that origin. The apocalyptic writings, it is said, "were the product of that mysterious sect the Essenes." "They were the secret sacred books of the Essenes." But the Essenes, according to our author, were not merely those ascetic communistic

bodies dwelling in remote parts of the country, with which we have usually connected the name; they were dispersed all over the country; they almost certainly had a locale at Nazareth; and around the strict observers of the vows of the sect there was a large mass of sympathisers less closely connected with it. Joseph and Mary may have belonged to this outer circle of Essenes, and our Lord may have been present at evening meetings of the Essenes of Nazareth, and there heard the sacred books, such as that of Enoch, which speaks of the Messiah as the "Son of Man," solemnly recited.

It is a great pleasure to see a work of such genuine learning, and such true perception of the problems of theology, issuing from a Scottish manse. Even by his title Mr. Thomson has done much to awaken an inquiry which must be faced in order to a true understanding of the Gospels. His theory, no doubt, will be much questioned. Is it legitimate, it must be asked, to speak of the Essenes in such a wide sense, as if all the genuine piety and all the longing for the promises, which existed at that time in Palestine, belonged to this one sect? Do the sources warrant the belief that all who were pious by other rules than those of the scribes and Pharisees and Sadducees might be called Essenes? Was the development of the national hope confined to this body? On these and on many points we have noticed in Mr. Thomson's book we cannot agree with him; but for all that we hail his work with genuine admiration and real pleasure, as a sign of good things to come for Scotland.

Click here for the Book of Enoch

Friday, June 5, 2020

Catholic Apologist Gary Michuta on the NWT Bible and John 1:1

Here, humorously (about the 18:35 mark in the first video) William Hemsworth states; "They add the word 'a god' instead of 'the word as with God the word was a god.'" I don't think this is what he was trying to saying, but I like Freudian slips as much as the next guy.

I believe the insinuation was that the New World Translation added the letter/word "a" here at John 1:1c. They never go on the explain in this segment that the Greek does not have indefinite articles, only definite articles. In English, adding the indefinite article to the translation is required to complete the sense. For instance, the Catholic New American Bible adds the "a" five times in John chapter 1 alone (John 1:6, 13, 30, 32, 47) even though that "a" was not in the Greek text. I could rant that this should not be so, but that would be silly and disingenuous.

The two then try to tie John 1:1 to John 20:28, however, the construction of the two Scriptures are quite different. John 1:1 has two gods mentioned, one has the definite article (the) and the other does not. The god that does not have the article is said to be WITH the god that has the article. This differentiation is very important and deliberate. Again, the second god mentioned is said to WITH "the god." You cannot be the same god that you are WITH.

The second god mentioned is also a predicate nominative that precedes the verb.

The Gospel of John has other examples of pre-verbal anarthrous predicate nominatives, over half of which are translated with the indefinite article "a." For example:

John 4:19 has PROFHTHS EI SU which translates to: "you are a prophet."

John 6:70 has DIABOLOS ESTIN which translates to: "is a slanderer."

John 8:34 has DOULOS ESTIN which translates to: "is a slave."

John 8:44 has ANQRWPOKTONOS HN which translates to "a murderer."

John 8:44 has EUSTHS ESTIN which translates to "he is a liar."

John 8:48 has SAMARITHS EI SU which translates to "you are a Samaritan."

John 9:8 has PROSAITHS HN which translates to "as a beggar."

John 9:17 has PROFTHS ESTIN which translates to "He is a prophet."

John 9:24 has hAMARTWLOS ESTIN which translates to "is a sinner."

John 9:25 has hAMARTWLOS ESTIN which translates to "he is a sinner."

John 10:1 has KLEPTHS ESTIN which translates to "is a thief"

John 10:13 has MISQWTOS ESTIN which translates to "a hired hand."

John 12:6 has KLEPTHS HN which translates to "he was a thief."

John 18:35 has MHTI EGO IOUDAIOS EIMI which translates to "I am not a Jew, am I?"

John 18:37 has BASILEUS EI SU which translates to "So you are a king?"

John 18:37 also has BASILEUS EIMI EGW which translates to "I am a king."

Notice the indefinite article "a" is inserted here in most Bibles, in all of these examples, even though the Greek does not have an indefinite article.

It had to be added because the English, and common sense (just as at John 1:1) demands it.

Now let's move on to John 20:28.

Jn 20:28 reads in the Greek: hO KURIOS MOU KAI hO QEOS MOU (the lord of me and the god of me) This type of wording is important as it actually creates a separation quite often. Let's look at other possessive pronouns repeated for perspicuity:

Mt 12:47, H MHTHR SOU KAI OI ADELFOI SOU/the mother of you and the brothers of you

49 H MHTHR MOU KAI OI ADELFOI MOU/the mother of me and the brothers of me

Mark 3:31, H MHTHR AUTOU KAI OI ADELFOI AUTOU/the mother of him and the brothers of him

32 H MHTHR SOU KAI OI ADELFOI SOU/the mother of you and the brothers of you

34 H MHTHR MOU KAI OI ADELFOI MOU/the mother of me and the brothers of me

Mk 6:4 TH PATRIDI AUTOU KAI EN TOIS SUGGENEUSIN AUTOU/the father of him and the relatives of him

7:10 TON PATERA SOU KAI THN MHTERA SOU/the father of you and the mother of you

Lk 8:20 H MHTHR SOU KAI OI ADELFOI SOU/the mother of thee and the brothers of thee

Lk 8:21 MHTHR MOU KAI ADELFOI MOU/mother of me and brothers of me

Jn 2:12 H MHTHR AUTOU KAI OI ADELFOI [AUTOU] KAI OI MAQHTAI AUTOU/the mother of him and the brothers of him and the disciples of him

Jn 4:12 OI UIOI AUTOU KAI TA QREMMATA AUTOU/the sons of him and the cattle of him

Acts 2:17 OI UIOI UMWN KAI AI QUGATERES UMWN/the sons of you and the daughters of you

Rom 16:21 TIMOQEOS O SUNERGOS MOU KAI LOUKIOS KAI IASWN KAI SWSIPATROS OI SUGGENEIS MOU/Timothy the fellow-worker of me of me and Lucius and Jason and Sosipater the kinsmen of me.

1 Thess. 3:11 QEOS KAI PATHR HMWN KAI O KURIOS HMWN IHSOUS/God and Father of us and the Lord of us Jesus.

2 Thess. 2:16 O KURIOS HMWN IHSOUS CRISTOS KAI [O] QEOS O PATHR HMWN/the Lord of us Jesus Christ and the God the Father of us

1 Tim. 1:1 QEOU SWTHROS HMWN KAI CRISTOU IHSOU THS ELPIDOS HMWN/God savior of us and Christ Jesus the hope of us

2 Tim 1:5 TH MAMMH SOU LWIDI KAI TH MHTRI SOU/the grandmother of you Lois and the mother of you Eunice

Heb 8:11 EKASTOS TON POLITHN AUTOU KAI EKASTOS TON ADELFON AUTOU/each one the citizen of him and each one the brother of him

Rev 6:11 OI SUNDOULOI AUTWN KAI OI ADELFOI AUTWN/the fellow-slaves of them and the brothers of them

As we can see, when this same construction is used, it is quite often referring to TWO different people or parties.

Theodore of Mopsuestia argued that the words were not addressed directly to Jesus but were uttered in praise or exclammation of God the Father. Perhaps he was correct. Catholics Gary Michuta and William Hemsworth snicker when the Witnesses repeat this argument, but Theodore of Mopsuestia was actually a Catholic Bishop.

Augustine in "Tractate CXXI" stated: "Thomas answered and said unto Him, My Lord and my God." He saw and touched the man, and acknowledged the God whom he neither saw nor touched; but by the means of what he saw and touched, he now put far away from him every doubt, and believed the other."

Others have also taken Thomas's exclamation as directed towards the Father, hence you have, "My Master, and my God" as in the 20th Century NT.

Winer, as does Beza, thinks it is simply an exclamation, not an address. (see G.B. Winer, A Grammar of the Idiom of the New Testament, 1872, p. 183

Why would they say this? Perhaps it is because at John 20:28 the nominative form KURIOS is used, while the vocative form KURIE is used mainly in direct address.

Other thoughts on John 20.28:

Brown reads it as "my divine one" The Gospel According to John, 1966

Burkitt paraphrases it as "It is Jesus himself, and now I recognize him as divine."

While I may not agree with Harris on everything, he does say, "Although in customary Johannine and NT usage (O) QEOS refers to the father, it is impossible that Thomas and John would be personally equating Jesus with the Father, for in the immediate historical and literary context Jesus himself has explicitly distinguished himself from God his Father." p. 124

"It is extremely significant that on the one occasion where there is no argument, in the case of Thomas, the statement is not a theological proposition but a lovers cry; it is not the product of intellectual reasoning but of intense personal emotion." p. 33, Jesus As They Saw Him, by William Barclay

John Martin Creed, as Professor of Divinity in the University of Cambridge, observed: "The adoring exclamation of St. Thomas 'my Lord and my God' (Joh. xx. 28) is still not quite the same as an address to Christ as being without qualification God, and it must be balanced by the words of the risen Christ himself to Mary Magdalene (v. Joh 20:17): 'Go unto my brethren and say to them, I ascend unto my Father and your Father, and my God and your God.'"

The translator Hugh J. Schonfield doubts that Thomas said: "My Lord and my God!" And so in a footnote 6 on John 20:28 Schonfield says: "The author may have put this expression into the mouth of Thomas in response to the fact that the Emperor Domitian had insisted on having himself addressed as 'Our Lord and God', Suetonius' Domitian xiii."—See The Authentic New Testament, page 503.

Margret Davies says in her book RHETORIC AND REFERENCE IN THE FOURTH GOSPEL, 125-126,

"Naturally, the interpretation of Thomas's words was hotly debated by early church theologians who wanted to use it in support of their own christological definitions. Those who understood "My Lord' to refer to Jesus, and 'my God' to refer to God [the Father], were suspected of heresy in the 5th cent CE. Many modern commentators have also rejected that interpretation and instead they understand the confession as an assertion that Jesus is both Lord and God. In doing so they are forced to interpret 'God' as a reference to LOGOS. But it is perfectly for Thomas to respond to Jesus' resurrection with a confession of faith both in Jesus as lord and in God who sent and raised Jesus. Interpreting the confession in this way actually makes much better sense in the context of the 4th gospel. In 14:1 belief in both God and in Jesus is encouraged, in a context in which Thomas is particularly singled out.... If we understand Thomas's confession as an assertion that Jesus is God, this confession in 20:31 becomes an anti-climax."

And what is that anti-climax at John 20:31? "These are recorded so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God." New Jerusalem Bible

John 1 begins with the Logos (Jesus) as a subordinate god, an only-begotten god, and John 20 ends with his declaration as the Son of God.

Isaac Newton on This Day in History

Isaac Newton's Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture by Henry Green 1856

https://newworldtranslation.blogspot.com/2017/11/isaac-newtons-two-notable-corruptions.html

Isaac Newton's Rejection of the Trinity Doctrine

https://newworldtranslation.blogspot.com/2018/07/isaac-newtons-rejection-of-trinity.html

Unitarians in History by Minot Savage 1898

https://newworldtranslation.blogspot.com/2019/02/unitarians-in-history-by-minot-savage.html

Thursday, June 4, 2020

100 Bibles You're Not Supposed to Read (Download)

Only $5.00 - You can pay using the Cash App by sending money to $HeinzSchmitz and send me an email at theoldcdbookshop@gmail.com with your email for the download. You can also pay using Facebook Pay in Messenger

Books Scanned from the Originals into PDF format - For a list of all of my digital books on disk click here

Join my Facebook Group - Contact theoldcdbookshop@gmail.com for questions

Books are in the public domain. I will take checks or money orders as well.

Contents:

These Bibles claim to have been translated with the help of the Spirit World, a big No-No for many Christians:

The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ as Revised and Corrected by The Spirits, by Leonard Thorn 1861

The Holy Scriptures, Containing the Old and New Testaments, An Inspired Revision of the Authorized Version, by Joseph Smith 1867

The New Testament Revised and Translated, by A. S. Worrell 1904

“...the writer, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit (as he believes), undertook the immensely responsible task of furnishing to the public, a correct and literal translation of these Scriptures, put up in good style, with brief notes designed to help the ordinary Christian, who has no knowledge of the original Greek.”

The Apocalypse Unsealed by James Pryse Being an Esoteric Interpretation and a New Translation 1910

Revealed Translation of John's Revelation Given By Jesus Christ to Archie Inger 1908

In 1953 Church-goers in Rocky Mount, North Carolina burned copies of the Revised Standard Version because it had removed the word "virgin" from Isaiah 7:14, but that Bible was not the first one. Included on this disk you have:

Isaiah in Modern Speech by John McFadyen 1918

The 24 books of the Holy Scriptures by Isaac Leeser 1922 (young woman)

The Holy Scriptures - Jewish Publication Society 1917 (young woman)

The prophecies of Isaiah, a new translation by T.K. Cheyne 1882 (young woman)

The Holy Bible by Samuel Sharpe 1883 (young woman)

A new translation of the Hebrew prophets (Isaiah) by George R Noyes 1868 (damsel)

The Weymouth New Testament 1909 (has even removed "virgin" from Matthew 1:23)

In the early 18th Century John Mill produced a Biblical Text that announced 30,000 variants in the Bible. The fact that there might be so many errors in the Bible disturbed a lot of people at the time. What followed was a spate of Bible versions with CORRECTIONS and IMPROVMENTS, which are included on this disk:

The Authorized Version with 20,000 Emendations by John Conquest 1841

The Commonly Received Version of the New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ with several hundred emendations by Spencer Houghton Cone and William H. Wyckoff

The Corrected English New Testament: A Revision of the "Authorised" Version using Nestle's Resultant Greek Text by Samuel Lloyd 1905

The New Testament - the Authorized Version Corrected by Sir Edward Clarke 1913

The New Testament for English Readers Containing the Authorized Version with Marginal Corrections of Readings and Renderings, Marginal References and a Critical and Explanatory Commentary 1868 Volume 1 by Henry Alford

The New Testament for English Readers Containing the Authorized Version with Marginal Corrections of Readings and Renderings, Marginal References and a Critical and Explanatory Commentary 1868 Volume 2 by Henry Alford

The New Testament for English Readers Containing the Authorized Version with Marginal Corrections of Readings and Renderings, Marginal References and a Critical and Explanatory Commentary 1868 Volume 3 by Henry Alford

The New Testament for English Readers Containing the Authorized Version with Marginal Corrections of Readings and Renderings, Marginal References and a Critical and Explanatory Commentary 1868 Volume 4 by Henry Alford

The New Testament of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ: the Common English version corrected by the final committee(1865) American Bible Union Version by American Baptist Publication Society

The Webster Bible (searchable pdf)

Webster’s Revision of the King James Bible was translated by Noah Webster and published in 1833. It is nearly identical to the KJV except for what Webster viewed to be corrections of the worst flaws of the text from the standpoint of an educator.

The Primitive New Testament 1745 by William Whiston

Whiston is best known for his translation of Josephus. Here he follows the KJV except where it departs from the "primitive" text.

Isaiah of Jerusalem in the authorized English version with Corrections and Notes, by Matthew Arnold 1883

THREE BIBLES - Scholarship and Inspiration Compared.

An Arrangement in Parallel Columns of Prominent Passages from the King James' and Revised Versions of the Bible, as well as the Holy Scriptures, translated by Inspiration through Joseph Smith by ELDER R. ETZENHOUSER 1903 (Great section in the back on how Bible Scholars really view the Bible)

The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments now translated from Corrected texts by Benjamin Boothroyd 1853

Many websites denounce Bible Versions that change proof texts for the Divinity/Deity of Christ, even calling them Arian-Based Versions. The Versions on this disk that appear to this are:

Newcome's Corrected New Testament 1808 (has "the Word was a God" at John 1:1)

Abner Kneeland's New Testament 1823 (has "the Word was a God" at John 1:1)

Moffatt New Testament

John 1:1 has "Logos was Divine" and John 8:58 has "I have existed before Abraham was born."

The Emphatic Diaglott 1870 (has "the Word was a God" at John 1:1)

The Bible in Modern English by Ferrar Fenton 1901 (this Bible has watered down the Deity of Christ at Matthew 2:2, Acts 20:28, Romans 9:5. Hebrews 1:6, 8)

The Emphasized Bible, Volumes 1,2,3,4 by Joseph Bryant Rotherham 1897, (denies Christ's Deity at Matt 2:2, Acts 20:28, Romans 9:5, Titus 2:13 and 2 Peter 1:1)

The New Testament by George Noyes 1869 (denies the Deity of Christ at Matt 2:2, Acts 20:28, Romans 9:5, Titus 2:13, Hebrews 1:6 and 2 Peter 1:1)

The New Testament by Gilbert Wakefield 1820 (denies the Deity of Christ at Matt 2:2, Acts 20:28, Titus 2:13, Hebrews 1:6, 8) Poor quality scan

The New Testament by H Heinfetter 1868 (denies the Deity of Christ at John 1:1, 8:58, Titus 2:13, Hebrews 1:8)

plus, The New Testament by George Barker Stevens

One of the hallmarks of Liberal Bible Versions is that they water down any threat of Hell. The following Bibles on this disk do not mention the word "Hell" at all and more closely follow the original languages:

20th Century New Testament 1901

New Testament by Jonathan Morgan 1848

The Holy Scriptures of the Old Covenant by Wellbeloved Volume 1 1862

The Holy Scriptures of the Old Covenant by Wellbeloved Volume 2 1862

The Holy Scriptures of the Old Covenant by Wellbeloved Volume 3 1862

Abner Kneeland New Testament 1823

A New and Corrected version of the New Testament by Rodolphus Dickinson 1833

A New and Literal Translation from the Original Hebrew by Julius Bates 1773

The Emphasized Bible by Joseph B Rotherham Volume 1 1916

The Emphasized Bible by Joseph B Rotherham Volume 2 1916

The Emphasized Bible by Joseph B Rotherham Volume 3 1916

The Emphasized Bible by Joseph B Rotherham Volume 4 1916

Charles Thomson Septuagint Volume 1 1904

Charles Thomson Septuagint Volume 2 1904

The Holy Bible in Modern English by Ferrar Fenton 1903

The Gospels by Nathaniel.Scarlett 1798

The New Covenant by JW Hanson 1884

The Emphatic Diaglott by Benjamin Wilson 1870

Weymouth's New Testament

The Holy Scriptures Jewish Publication Society 1917

Youngs Literal Bible 1898

The Interlinear Literal Translation Of The Greek New Testament - Thomas Newberry, George Berry

The Coptic Version of the New Testament by G Horner 1898 Volume 1

The Coptic Version of the New Testament by G Horner 1898 Volume 2

The Coptic Version of the New Testament by G Horner 1898 Volume 3

The Coptic Version of the New Testament by G Horner 1898 Volume 4

The New Testament by James Moffatt 1922

The Catholic Epistle of St. James: A Revised Text with Translation, Introduction, and Notes (1876) Francis Tilney Bassett

The Primitive New Testament 1745 by William Whiston (

Whiston is best known for his translation of Josephus. Here he follows the KJV except where it departs from the "primitive" text.)

The Book of Genesis in English-Hebrew 1828 (

Genesis traditionally has 4 scriptures that use the word HELL: Genesis 37:35, Genesis 42:38, Genesis 44:29, Genesis 44:31)

The Book of Genesis and Part of the Book of Exodus by Henry Alfrod 1872

A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the book of Genesis, with a New Translation 1873 by James Murphy

An Interpretation of Genesis, Including a Translation into Present-day English by Franklin Ramsay 1911

The Book of Genesis - a Translation from the Hebrew by F Lenormant 1886

The Hebrew Text and a Latin version of the book of Solomon, called Ecclesiastes plus newly arranged English version of Ecclesiastes by T Preston 1845

Ecclesiastes traditionally has scriptures at Eccl. 9 that use the word HELL

The Book of Ecclesiastes with a new translation (1890) by Samuel Cox

The Book of Ecclesiastes - a New Metrical Translation by Paul Haupt 1905

A gentle cynic - being a translation of the Book Ecclesiastes (1919) by Morris Jastrow

Ecclesiastes considered in relation to modern criticism, and to the doctrines of modern pessimism, with a critical and grammatical commentary and a revised translation by Charles Wright 1883

The Psalms in Modern Speech by John McFadyen 1916

The Psalms by John De Witt 1891

Psalms traditionally has scriptures that use the word HELL in place of Sheol.

The Book of Psalms, a new English translation by HH Furness 1898

The Book of Psalms - a new translation by TK Cheyne 1895

The Messiah as Predicted in the Pentateuch and Psalms - a New Translation by J Robert Wolfe 1855

An Attempt Towards an Improved Translation of the Proverbs from the original Hebrew, with notes, critical and explanatory by George Holden 1819 (uses HADES instead of Hell)

The Prophecies of Isaiah A New Translation by TK Cheyne Volume 1 1884

The Prophecies of Isaiah A New Translation by TK Cheyne Volume 2 1884

(Uses Sheol instead of Hell)

A literal translation of the Prophets from Isaiah to Malachi Volume 1 by Robert Lowth

A literal translation of the Prophets from Isaiah to Malachi Volume 2 by Robert Lowth

A literal translation of the Prophets from Isaiah to Malachi Volume 3 by Robert Lowth

A literal translation of the Prophets from Isaiah to Malachi Volume 4 by Robert Lowth

A literal translation of the Prophets from Isaiah to Malachi Volume 5 by Robert Lowth 1831-1836

The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel: A New English Translation by Crawford Howell Toy 1899

(Uses Sheol instead of Hell)

The Revelation of John; an Interpretation of the Book with an introduction and a translation by Charles Whiting 1918

The Revelation given to St. John the Divine by John H Latham 1896

The Apocalypse of St. John done into modern English by Ralph Sadler 1891

The Gospel in Brief by Leo Tolstoy 1896

The Sacred Scriptures in Hebrew and English Volume 1 - A New Translation by David de Aaron de Sola 1844

The Englishman's Greek New Testament giving the Greek text of Stephens 1550, with the various readings of the editions of Elzevir 1624, Griesbach, Lachmann, Tischendorf, Tregelles, Alford, and Wordsworth: together with an interlinear literal translation, and the Authorized Version of 1611 (1896)

(While it has the King James on one side, the Interlinear translation underneath the Greek text correctly translated gehenna, tartarus, etc accordingly)

The Acts of the Apostles, being the Greek text as revised by Drs. Westcott and Hort by Thomas E Page 1886:

Has single word translations, like this following of Hades on p.91:"represents the Hebrew sheol, 'the grave' (e.g. Gen. xxxvii. 35), a very negative word, 'the place not of the living but of the dead'. It is often used locally as the opposite of 'heaven', e.g. Job xi. 8, and cf. Matt. xi. 23; Luke x. 15. Neither it, nor hades, denotes a place of punishment; even in Luke xvi. 23 'in hell he lift up his eyes', the marked addition of the words UPARCWN EN BASANOIS shews that the idea of torment is in no way involved in the word."

Comes with a free Septuagint Interlinear Bible broken down by book.

The American Standard Version 21st Century Edition Version 2.0.1 by Heinz Schmitz

Plus You Get:

An Inquiry into the Scriptural import of the words Sheol, Hades, Tartarus, and Gehenna - all translated Hell in the common English version by Walter Balfour 1832

The Doctrine of eternal hell torments overthrown by Thomas Whittemore 1833

The Bible Hell by JW Hanson

The Bible Vindicated against Modern Theology by a Christadelphian 1875

There Hereafter: Sheol Hades and Hell by James Fyfe 1890

The Occurence of Sheol in the Old Testament by Heinz Schmitz

Biblical Psychology by Jonathan Forster 1873

The State of the Dead and the Destiny of the wicked by Uriah Smith

The Intermediate state by Henry Grew

Hades or, The intermediate state of man By Henry Constable 1864

What is the Future Condition of the Wicked, article in The Methodist quarterly review 1872

Death not Life or, The theological hell and endless misery disproved by Jacob Blain 1853

The Woman's Bible by Elizabeth Cady Stanton

("The Bible estimate of woman is summed up in the words of the president of a leading theological seminary when he exclaimed to his students, "My Bible commands the subjection of women forever."")

Folk-lore in the Old Testament Volume 1 by James Frazer 1918 (Pagan Flood stories, the mark of Cain etc)

Folk-lore in the Old Testament Volume 2 by James Frazer 1918 (the marriage of cousins, the Witch of Endor, etc)

Folk-lore in the Old Testament Volume 3 by James Frazer 1918 (the high places in Israel, etc)

A Genetic Study of the Spirit-phenomena in the New Testament by Elmer Zaugg 1917

For many Fundamentalist and Evangelical Christians no Greek text is so despised as the Westcott and Hort Greek Testament, this is also include on this disk, as is the Catholic Douay Bible with its Apocrypha and copious Catholic notes.

Wednesday, June 3, 2020

The Trinity and the "Mystery" Argument

POPULAR FALLACIES OF TRINITARIANISM.

I.—TRINITARIAN FALLACY CONCERNING MYSTERY; OR, MYSTERY NO ARGUMENT IN PROOF OF THE TRINITY.

As to what is called "the mystery of the Trinity," though strictly a religious matter, and pretended to be purely a matter of divine revelation, it is yet a thing confessedly nowhere so much as once named in Scripture, either as a mystery or not a mystery. It is freely confessed, as it must be by all its abettors, to be purely a matter of inference—a theory which they have assumed to explain certain things in Scripture which they think cannot be rightly accounted for otherwise; and because we cannot comprehend the works of God—and far less God himself—so they think the nature of God being so much a mystery, we should just believe as they do, and not presume to question their opinion concerning that mystery. This, under whatever plausible garb it may be put forward, is always the real amount of the argument which is attempted to be passed off in every one of those stale appeals that are made to mystery in behalf of Trinitarianism; and as it is a conclusion between which, and the premises, we certainly cannot see the least connexion, so it is one to which we at once demur, and maintain that we have a right and a duty upon us to prove all things, and hold fast only that which is good. 1 Thess. 5:21.

In speaking of mystery—just as if that could solve and silence every objection to the Trinity—they sometimes affect to be very rational and philosophical, arguing, in very plausible terms, how we must admit mystery in the works of God; and how much more reason have we to admit it in God himself. Now, we must freely admit it in both; but we tell them that whatever mysteries may be in nature, no philosopher appeals to mystery for the support of any notion or theory which he may form of the laws of nature; nor, if he did so, would he be allowed, for a moment, the right of such an appeal? What, for example, is more mysterious in nature than the principle of gravitation? Now, we have a theory on this subject, as applied, for instance, in the science of astronomy, to account for the motions of the heavenly bodies. But what rational defender of this theory would pretend to answer any objections that might be brought against it by saying, that it is a mystery—that we should not presume to question the received theory of this principle, because, forsooth, it is one of deep and impenetrable mystery? What man of science is there who would not spurn, with contempt, such a plea? and if the theory could not be defended altogether without such a plea, it behoved of necessity to fall to the ground, and deservedly so. On the subjects of light and vision, and of the constitution of the human mind, which are all of them matters of great mystery, we have different theories—some of them, of course, open to objection: so on numberless other mysterious subjects, we have different theories, all of them less or more objected to; but no one thinks of quashing or putting down objections to his particular theory, by alleging that the subject is a mystery. No: such a thing is utterly out of the question. It was reserved for Trinitarian theorists alone to seek to defend their peculiar theory by the help of mystery, and, at the same time, modestly to assume to themselves the character of being the only reasonable, orthodox, right-hearted, and truly pious men!

It is one thing to admit mystery in the nature of God, and another to admit mystery as an argument for any opinion of man concerning that nature. Though always confounded by Trinitarians, the cases are wide as the poles asunder. We admit mystery, in the nature of God, as freely as they do, but deny mystery as an argument for any theory or notion of man, concerning that nature, or any nature whatever. In all this we are perfectly consistent, both with ourselves and with the principles of sound philosophy, and desire our opponents to show where their consistency with either lies.

Moreover, we would remind them of her who has mystery written on her forehead—that mystery is great Babylon's motto—the chief corner-stone of bigotry and priestcraft; and it belongs to "Mystery, Babylon the Great," and to her philosophy only, to seek to impose her unreasonable dogmas on mankind by the dark device of mystery. Where mystery begins, all knowledge, and all revelation ends. The Scripture notion of a mystery is that of a new truth, or something that is a secret until it be revealed; but, when once it be revealed, it ceases to be a mystery. "Behold," says the apostle, "I show you a mystery," (a new truth, which they did not know till he told them.) "To you it is given," says Christ to his disciples, "to know the Mysteries," (the secrets or new doctrines) "of the kingdom of heaven." Bet the mysteries of Babylon the Great are quite different: they are things that cannot be revealed or given to any to know; being professedly incomprehensible; but, in real truth, they are mere confusion and contradiction—quite like the name Babylon itself—which is a name of confusion. Babylon comes from Babel, which signifies confusion; and "Mystery Babylon," signifies mystery confusion, or confused mystery.

Let us, therefore, have no more of mystery in the shape of argument; for, it is a thing below all contempt to seek to argue from mystery, for anything whatever, unless we mean to be sceptics, saying, All is mystery in the nature of God, and that we know nothing, and need trouble ourselves nothing about the matter—a conclusion, alas! to which there is reason to fear that too many have been driven by the hard and tremendous thoughts of God, to which the notion of a Trinity has given birth. Witness, in particular, their unreasonable heart-withering and terrific notions of original sin, and predestination of a helpless non-elect world of mankind to eternal torment—their wild absurdities of transubstantiation—of bowing to crosses and images, as if they were gods—of worshipping and praying to the Virgin Mary, under the profane heathenish titles of "Holy Mother of God," and "Queen of Heaven," with a mass of other nauseous matter of the same kind, all finding a ready plea in mystery; and being the very flower and first-fruits of Trinitarianism as it first began to appear in maturity in the days of Chrysostom, Jerome, and Augustine.

Nature, to which Trinitarians so much appeal for mystery, is full of secrets, but no mysteries of their kind, which are palpable contradictions. Taking mystery in this, its scriptural and rational sense, it makes nothing in favour of scepticism; for it is always to be remembered, that however secret or mysterious a thing may be in one aspect, this is not at all to hinder us from viewing it in other aspects, and ascertaining with certainty every fact concerning it, that is necessary for us to know; and it is only from known facts that we can draw any just conclusions: so far as mystery is concerned in anything, it makes not for any one conclusion, or any one opinion, more than another. It makes for nothing, save the modest suspension of opinion about the matter, and for calmly instilling the needful lesson of humility, charity, and Christian forbearance, which are alike remote from the cold frigidity of scepticism, on the one hand, and from the fiery bigotry of Trinitarianism, on the other.

Whenever we form a theory of any subject, it matters not how mysterious the subject may be, that is not the question. We have formed A Theory, and that is the question, and that alone; and that must be defensible without reference to mystery, or not at all. In the case of two men forming different theories of the same subject, there is not, and cannot be, a shadow of reason beyond his own dogmatic conceit, why the one man should claim the mystery of the subject for his theory, any more than the other man should claim it for his. So far as mere mystery is concerned, both have an equal claim or none at all. The truth is, that once admit mystery as an argument for one opinion, and there is no opinion, however absurd, that may not claim the same privilege: and this is the whole upshot of the matter about mystery. And let Trinitarians take this along with them, that we admit mystery, in the nature of God, as freely as they do; but deny mystery as an argument for the truth of anything that we do not already perfectly know to be true without it; and that we reject their theory just for this very reason, that they cannot defend it without mystery—that they cannot defend it by honest Scripture argument, without recourse to this sophistical plea of mystery—this hollow and dark device of priestcraft, by which it has sought, in every age, to enslave the human mind, and which is no other than raising a mist, and a casting of dust in the people's eyes that they may not see the truth.

One of the first texts that shook my belief in the Trinity was, Phil 2:9—"Wherefore God also hath highly exalted him," &c. These words plainly imply that God and Christ are two distinct beings —that Christ is a being distinct from, and inferior to, the God that highly exalted him. This is a truth so self-evident, that to deny it, we may as well deny that two and two make four. To speak of Christ's human nature as being meant only here, is nothing to the purpose; it is begging the question. It was not the human nature that humbled itself to take human nature. God highly exalted him, and him only, that humbled himself to take a servant's form. It was not the form he exalted, but him that took the form. This is unquestionably the fact; and all the attempts made to evade it, by the abettors of the common system, only involve them in a mass of quibbling and equivocation. The stale device of mystery to which they resort, as a plea for their system, we have sufficiently seen, does them no good. Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, and Harvey, have been among the most illustrious in forming theories of certain departments of the laws of nature, which have fully stood the test of investigation, but which, at the first, had all to contend with the bitterest opposition and prejudice of the day; but none of these illustrious names, however bitterly opposed and persecuted some of them were, even advanced the plea of mystery in support of his theory. Never, for a moment, did they attempt to silence objection in such a manner, or hint at such a thing—nor has any true philosopher ever done so. It is in vain then for our opponents to advance such a plea for their favourite theory; a plea which they themselves would scorn to advance for any theory in any other branch of science whatever.

Whatever the Scripture says about mystery, taking the term in any sense you please, it nowhere represents the unity of the one God as a mystery, any more than the unity of the one Lord, the one faith, the one baptism, or any other unity whatever. It makes no distinction between the numerical oneness of God, and that of any other single intelligent being in the universe. When it speaks of one man, no body doubts the meaning, or talks of mystery; and when it speaks of one God, it sets no guard or limitations in the one case more than the other. It asserts God to be one in the common numerical sense of the term, in opposition to polytheism, which maintains the contrary, that there are more gods than one. Moreover, the Scripture having once asserted that God is one, never varies from that assertion, nor ever stops to explain it, but leaves it wholly to ourselves to determine the meaning of the word one, as applied to God, the same as when applied to any other single intelligent being. And the question then is, in what sense ought we to take the word one, as applied to God? whether in the plain popular sense that a child would think of on hearing of "one God and Father," or in the complex speculative Trinitarian sense, that no child or plain person would think of without suggestion from some other source than Scripture? I affirm, in the plain popular sense, without a doubt, as the Scriptures in all practical matters are invariably written in the plain popular style for the use of plain illiterate people, for little children, and those like them, for the mass of mankind, who are incapable of entering into any farfetched, abstruse speculation—especially where nothing of the kind is suggested to them. While the Scriptures of the Old Testament often expostulate with heathens for their polytheism, and tell them most expressly that there is but one God, they never give them the most distant hint of his being a Trinity, three in one, or one in any other than the common popular sense in which they were accustomed to take each of their own gods by himself as one, or one undivided person, in the Unitarian sense. And unless the heathen were accustomed to view each of their own false gods as a Trinity, it is impossible they could otherwise, from all that the Bible says to them on the subject, conceive to themselves the notion of the true God being a Trinity, without giving way to a new imagination, alike unheard of in the Bible and their own system.

In connexion with this subject, it is worthy of particular remark, how Jesus commends little children as a type of the character of his true disciples, saying, "Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me; for of such is the kingdom of heaven." Matt, 19:14. "Verily, I say unto you, whoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child, shall in no wise enter therein." Luke 18:17. "Verily, I say unto you, except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven." Matt, 18:3. Now, let us think of this, and compare it with the fact, that no child or plain unprejudiced person, in reading the Scriptures by himself, without the teaching of Trinitarians, ever imagines God to be three in one, or one in any other than the common numerical or Unitarian sense. When a child, after knowing his earthly father, comes next to hear, in the simple words of Scripture, of "one God and Father of all," in heaven, he never dreams of his one heavenly Father being a Trinity, any more than his one earthly father. He never thinks of his heavenly Father any otherwise than as a Unitarian, till he has been taught his mistake by some book or creed, or advocate of Trinitarianism. Never till then does he find out his mistake, however often, or however carefully he may read his Bible. He may find many things there to puzzle him—but never does that theory occur to him without suggestion from some foreign quarter. Indeed, it were most unlikely, if not morally impossible, that a doctrine which took centuries of subtle speculation and discussion among learned theologians and polemics, to bring it to its present state of perfection, should be stumbled upon in a lifetime's reading of the Bible alone, by plain illiterate people that had never heard of such speculation. During childhood and youth it was certainly my own simple belief—to which belief I am now returned—that my heavenly Father was one undivided person, and one God—the same as my earthly father was one undivided person, and one man; and this, I am satisfied, is the simple belief of every child on being told of God, or reading of him in his Bible, by himself, without the sophistication of Trinitarians; and, that he never imagines anything to the contrary, till his mind has first been brought over by a series of training to their way of thinking. Whatever new or peculiar ideas might occur to him in reading his Bible, I am well satisfied that nothing of their strange and complex hypothesis would ever occur to him without their teaching. And, indeed, after all their training, I am quite convinced that the mass of the people, even serious people, unless immediately prompted by the words of some human creed, seldom or ever think of God as a Trinity, or in any other than the simple way in which Jesus himself would lead us to think, when he says, "I ascend unto my Father and your Father, and to my God and your God." John 20:17.

The hard, perplexing, unscriptural terms, which the doctrine of the Trinity so much requires for explaining it, put it far enough beyond the reach of common people to think of from the bare words of Scripture, and apart from all other considerations, go very far indeed to satisfy my own mind, that, as that doctrine cannot be expressed in Scripture language, so it is destitute alike of Scripture foundation. It must be allowed upon all hands, that the Bible says nothing about mystery or Trinity in the unity of God: and where then is the right of man to foist in mystery and Trinity where God has said nothing of either; and then to condemn his fellow-man who cannot fall down and worship the idol of his imagination? In a word, while Trinitarians will have God to be a Trinity, a three-one God, the Scriptures never speak of such a thing, but always -represent God simply as one, without the least mention of three,* or any number but One! [*The text of 1 John v. 7, about "three that bear record in heaven," is spurious, and has been unanswerably proved to be so.]

We, therefore, hold fast the Scripture number, and determinately reject all attempts to add to it, or to make God a being of any number but one. "To us there is but one God, the Father, of whom are all things." 1 Cor. 8:6. "There is one God and Father of all, who is above all, and through all, and in us all." Eph. 4:6. "There is one God, and one Mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus." 1 Tim. 2:5

T. G. (1847)

Newburgh, Aberdeenshire.

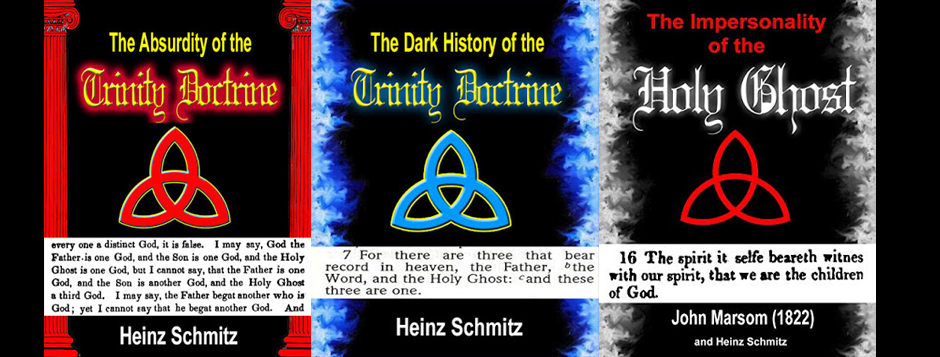

Buy: And the Word was a god: A New Book on the Most Disputed Text in the New Testament - John 1:1 and The Dark History of the Trinity, is now available on Amazon by clicking here...and both are only 99 cents

See also Christology & the Trinity Doctrine - Over 320 Books on the on TWO DVDroms

See also Christology & the Trinity Doctrine - Over 320 Books on the on TWO DVDroms

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)